April 14, 2020 SECTION OF LITIGATION No-Contact Orders in Parental Alienation Cases It is critical to understand why family courts order temporary no-contact periods between the favored parent who has been found to have engaged in alienating behaviors and the child. By Ashish Joshi Share this: ! "

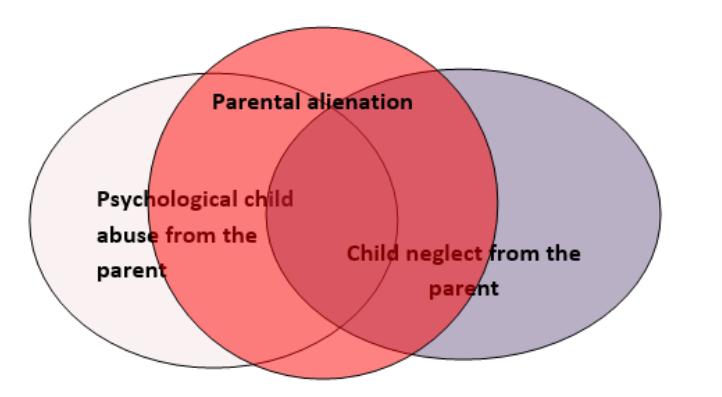

# Parental alienation is not new: The mental condition has been described in the legal cases since the early nineteenth century and in the scientific literature since the 1940s. See, e.g., “Westmeath v. Westmeath: The Wars Between the Westmeaths, 1812–1857,” in Lawrence Stone, Broken Lives: Separation and Divorce in England, 1660–1857, at 284 (1993); David M. Levy, Maternal Overprotection 153 (1943). One of the most widely accepted definitions of the condition is a “mental condition in which a child—usually one whose parents are engaged in a high-conflict separation or divorce—allies himself or herself strongly with an alienating parent and rejects a relationship with the ‘target’ parent without legitimate justification.” D. Lorandos, W. Bernet & R. Sauber, “Overview of Parental Alienation,” in Parental Alienation: The Handbook for Mental Health and Legal Professionals 5 (Lorandos, Bernet & Sauber eds., Charles C. Thomas Ltd. 2013). A Form of Emotional Abuse That Should Not Be Tolerated In defining parental alienation, family courts have focused on behaviors manifested by an alienating parent and the signs of alienation in the affected child: (1) the alleged alienating conduct, without any other legitimate justification, be directed by the favored parent, (2) with the intention of damaging the reputation of the other parent in the children’s eyes or which disregards a substantial possibility of causing such, (3) which proximately causes a diminished interest of the children in spending time with the non-favored parent and, 4) in fact, results in the children refusing to spend time with the targeted parent either in person, or via other forms of communication. J.F. v. D.F., 61 Misc. 3d 1226(A), 2018 N.Y. Slip Op. 51829(U) (N.Y. Sup. Ct. 2018). Courts have also used terms other than parental alienation to criticize the very behaviors underlying the condition but have chosen to call it by another name. For instance, in Martin v. Martin, the Nebraska Supreme Court found a custodial parent to have used “passive aggressive techniques” in undercutting the non-custodial parent’s relationship with the children. Martin v. Martin, 294 Neb. 106 (Neb. 2016). While the words “parental alienation” were not used, the In Meadows v. Meadows, the Michigan Court of Appeals focused on the behaviors of an alienating parent: “The process of one parent trying to undermine and destroy to varying degrees the relationship that the child has with the other parent.” Meadows v. Meadows/Henderson, 2010 WL 3814352 (Mich. Ct. App. 2010) (unpublished). In McClain v. McClain, the Tennessee Court of Appeals focused on the mental condition of the child: “The essential feature of parental alienation is that a child . . . allies himself or herself strongly with one parent (the preferred parent) and rejects a relationship with the other parent (the alienated parent) without legitimate justification.” McClain v. McClain, 539 S.W.3d 170, 182 (Tenn. Ct. App. 2017). In J.F. v. D.F., the New York Supreme Court attempted to define parental alienation by borrowing a chapter from the elements of the tort of intentional infliction of emotional distress and defined the condition to require that Nebraska court’s detailed discussion of the custodial parent’s alienating behaviors and strategies left little room for doubt that the court was addressing the phenomenon of parental alienation. Experts, too, have used different terms to describe these behaviors (see Lorandos, Bernet & Sauber, supra, at 8): [h]inder the relationship of the child with the other parent due to jealousy or draw the child closer to the communicating parent due to loneliness or a desire to obtain an ally. These techniques may also be employed to control or distort information the child provides to a lawyer, judge, conciliator, relatives, friends, or others, as in abuse cases. Id. at 15. Regardless of the varying definitions of parental alienation, or even nomenclature, the consensus among the courts is that “there is no doubt that parental alienation exists.” J.F. v. D.F., 61 Misc. 3d 1226(A), 2018 N.Y. Slip Op. 51829(U). More importantly, courts agree that it “is a form of emotional abuse that should not be tolerated.” McClain v. McClain, 539 S.W.3d at 200. In the For example, Dr. Stanley Clawar, a sociologist, and Brynne Rivlin, a social worker, use the terms “programming,” “brainwashing,” and “indoctrination” when describing the behaviors that cause parental alienation. Clawar & Rivlin, Children Held Hostage: Dealing with Programmed and Brainwashed Children (ABA Section of Family Law 2013). The authors explained that these behaviors Dr. Richard Warshak, a clinical professor of psychiatry, has used the term “pathological alienation” that results from such alienating behaviors: [a] disturbance in which children, usually in the context of sharing a parent’s negative attitudes, suffer unreasonable aversion to a person or persons with whom they formerly enjoyed normal relations or with whom they would normally develop affectionate relations. Warshak, “Social science and parental alienation: Examining the disputes and the evidence,” in The International Handbook of Parental Alienation Syndrome: Conceptual, Clinical and Legal Considerations 361 (R.A. Gardner, S.R. Sauber & D. Lorandos eds., 2006). end, the consensus among the courts, experts, and mental health professionals appears to be that parental alienation “refers to a child’s reluctance or refusal to have a relationship with a parent without a good reason.” W. Bernet, M. Wamboldt & W. Narrow, “Child Affected by Parental Relationship Distress,” 55 J. Am. Acad. Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 571, 575 (July 2016). Temporary No-Contact Orders—Necessary and Warranted in Alienation Cases Alienated children suffer from severe behavioral, emotional, and cognitive impairments. R. Warshak, “Severe Cases of Parental Alienation,” in Parental Alienation: The Handbook for Mental Health and Legal Professionals 5 (Lorandos, Bernet & Sauber eds., Charles C. Thomas Ltd. 2013). Specialized reunification programs (which are radically different from “therapy”) are designed to repair the damaged relationship between alienated parents and the children. They often require a temporary no-contact period between the favored parent and the children, together with the parent’s compliance with some conditions before the resumption of regular contact. Resumption of contact is dependent on the favored parent’s willingness and demonstrated ability to modify his or her alienating behaviors—behaviors that would no doubt sabotage the gains made during the reunification program in an absence of a no-contact order. Also, “optimal timing” to resume regular contact would depend on a number of factors, “such as the favored parent’s ability to modify behaviors that create difficulties for the children, the children’s vulnerability to feeling pressured to realign with a parent, the duration of the alienation or estrangement prior to the Workshop, and the favored parent’s past conduct and compliance with court orders.” Warshak (2010), supra, at note 95. In cases of severe parental alienation, experienced and knowledgeable clinicians recommend “a period of 3-6 months before regular contacts resume” between a formerly favored parent and the child “to allow a child to consolidate gains and work through the numerous issues that arise in living with the rejected parent free from the influence of the favored parent.” Id. While the regular (unsupervised) contact is held off for a limited period, therapeutically monitored contacts between a formerly favored parent and child may occur sooner. Id. It is critical to understand why family courts order temporary no-contact periods between the favored parent who has been found to have engaged in alienating behaviors and the child. When contact resumes, it usually occurs first during sessions with a professional who can monitor its impact on the child who is going through (or has just been through) a reunification program. Such precautions are necessary because research demonstrates that it is very hard for alienating parents to change their behaviors. If contact is restored prematurely or without proper safeguards, the children become “re-alienated,” reverting to their old behaviors and back to rejecting the target parent. Id. at 69. The pathology of parental alienation is so severe that some alienators “chose to go for months “without seeing [their] children or working towards meeting conditions for renewal of contact.” Id. Some refuse to cooperate with court orders and want “no contact with [the] children because [they] take their [the children’s] reconciliation with [the target parent] as a personal rejection.” Id. One “chose to cut off all contact with [the child] and said that when the boy turns 18 he could choose to renew contact.” Id. Repairing the Damaged Relationship Between the Alienated Child and the Targeted Parent Once a court determines a child has been alienated, it must make a decision as to what legal and mental health interventions are mandated in the best interests of the child. In making this decision, courts often face what British Columbia Justice Bruce Preston termed “a stark dilemma.” A.A. v. S.N.A., [2007] BCSC 594 (Can.). More than 10 years ago, Justice Preston wrestled with this dilemma: The probable future damage to M. by leaving her in her mother’s care must be balanced against the danger to her of forcible removal from the strongest parental connections she has . . . I conclude that the forcible removal of M. from her mother’s and her grandmother’s care has a high likelihood of failure, either because M. will psychologically buckle under the enormous strain or because she will successfully resist re-integration with her father. Id. at 84–87. Nonetheless, the Court of Appeals weighed in on the other side of this “stark dilemma,” disagreed, and found that the obligation of the court to make the order it determines to be in the best interests of the child “cannot be ousted by the insistence of an intransigent parent who is ‘blind’ to her child’s interests. . . . The status quo is so detrimental to M. that a change must be made in this case.” A.A. v. S.N.A., [2007] B.C.J. No. 1475; 2007 B.C.C.A. 364; 160 A.C.W.S. (3d) 500, at 8. In contrast to Justice Preston’s “stark dilemma,” family courts around the country, recognizing the severe psychological toll wreaked by parental alienation on the children, are increasingly open to providing aggressive but necessary intervention: That’s what we’ve been doing for nigh on 16 years. We’ve been working on this and working on it and we’ve been to counselors and therapists and doctors and courts In February 2020, an Indiana family court found that a father had engaged in severe parental alienation and domestic and family abuse. Given that the child was over 16 years of age, the court recognized that time was of essence in reuniting the child with the mother, the targeted parent. The court provided immediate and effective intervention: It gave the mother sole legal and primary custody, ordered the mother and the child to participate in a specialized reunification program that is designed for the alienation dynamic, ordered a 90-day no-contact period between the father and the child, and ordered the father to cooperate and comply with the recommendations of the reunification counselors. In re the Marriage of Wright and Wright, No. 53C08-1804-DC000203 (Monroe Cty. Cir. Ct. VIII, Ind. Feb. 6, 2020). In 2017, the Tennessee Court of Appeals affirmed a ruling where the trial court, upon finding severe parental alienation, ordered no contact between the minor child and the alienating parent (the father) “for at least 90 days” beginning with a reunification program. McClain v. McClain, 539 S.W.3d at 183. In addition, the alienating parent’s future parenting time with the child was conditioned on the parent’s compliance with the rules and recommendations of the reunification program counselor and the aftercare professional. Id. As the court found, the seemingly harsh but temporary no-contact period was a necessary step not only to give the child a realistic hope at reunification but also to protect the child from continued alienating behaviors. The court reasoned that the traditional therapy, counseling, education, and parenting coordination had yielded zero results and made a bad case worse: and more counselors and different therapists and more doctors and court. It’s a merry-go-round upon which we have all been for many, many years and it did not work. I have no reason to believe it’s ever going to work in the future.” Id. at 210. The court realized that the temporary, 90-day no-contact period, together with a specialized reunification program, was “most likely to result in a change in the pattern of parental alienation and therefore in the best interest of the children.” Id. at 211. Such a measure was necessary to facilitate reunification of alienated parents with alienated children and to “reduce the potential for sabotage.” Id. at 213. Separating Children from an Alienating Parent Found to Not Be Traumatic Research demonstrates that alienation abates when children are required to spend time with the parent they claim to hate or fear. R. Warshak, “Ten Parental Alienation Fallacies That Compromise Decisions in Court and in Therapy,” 46 Prof. Psychol.: Res. & Practice 235–49 (Aug. 2015). Despite this, lawyers, guardians ad litem, lawyer-guardians ad litem, children’s counselors, and other professionals predict dire consequences to children if the court fails to endorse their strong and strident preferences to avoid a parent. Usually, such predictions “are vulnerable to reliability challenges because the experts cite undocumented anecdotes, irrelevant research, and discredited interpretations of attachment theory.” Id. In dealing with such predictions, a court should consider the following: (1) No peer-reviewed study has documented harm to severely alienated children from the reversal of custody; (2) no study has reported that adults, who as children complied with expectations to repair a damaged relationship with a parent, later regretted having been obliged to do so; and (3) studies of adults who were allowed to disown a parent find that they regretted that decision and reported long-term problems with guilt and depression that they attributed to having been allowed to reject one of their parents. Id. (citing A.J.L. Baker, “The Long-Term Effects of Parental Alienation on Adult Children: A Qualitative Research Study,” 33 Am. J. Fam. Therapy 289–302 (July 2005)). Professionals who attempt to persuade courts not to separate children from an alienating parent (or oppose a temporary no-contact order between the alienating parent and the children) generally cite attachment theory to support their predictions of “trauma” or psychological damage to children. Such arguments are flawed, misleading, and “rooted in research with children who experienced prolonged institutional care as a result of being orphaned or separated from their families for other—often severely traumatic—reasons.” Id. (citing P.S. Ludolph & M.D. Dale, “Attachment in Child Custody: An Additive Factor, Not a Determinative One,” 46 Fam. L. Q. 1–40 (Spring 2012)). A consensus of leading authorities on attachment and divorce shows that this theory does not support generalizing the negative outcomes of traumatized children who lose both parents to a case involving parental alienation, where children leave one parent’s home to spend time with their other parent, under a court order. Id. Further, attorneys for targeted parents should challenge these experts to unpack their evocative jargon if they attempt to dissuade a court from intervening in an alienation case by using terms like “trauma” and “attachment.” Id. When these experts predict that the child will be “traumatized,” what they usually mean is that the child will be “unsettled.” Id. (citing J.A. Zervopoulos, How to Examine Mental Health Experts (ABA 2013)). Such pessimistic predictions not only lack empirical support but are willfully blind to the well-documented benefits of removing a child from an alienating parent whose behavior is considered psychologically abusive. Clawar & Rivlin, supra. Effective interventions provide experiences that help uncover the positive bond between the child and the targeted parent. “These experiences can help [the children] to create a new narrative about their lives, one that is more cohesive, more hopeful, and allows them to begin to see themselves in a new place.” Id. (citing C.L. Norton, “Reinventing the Wheel: From Talk Therapy to Innovative Interventions,” in Innovative Interventions in Child and Adolescent Mental Health 2 (C.L. Norton ed., Routledge 2011)). In Martin v. Martin, the Michigan Court of Appeals acknowledged how alienation behaviors are alarming and psychologically abusive: [T]hese are not minor disputes over contempt and parenting time. These are matters that could have a significant effect on the child’s life, including on her long-term mental and emotional health: having to maintain the perception of hatred and contempt toward her father—which she may or may not share with her mother—will undoubtedly affect her mental and emotional health as well as her long-term relationship with her father. Martin v. Martin, No. 349261, slip op. at 9 (Mich. Ct. App. 2020). Given the significant damage to children who remain alienated from a parent, removing the child from an alienating parent’s custody and entering a temporary no-contact order between the two is ultimately “far less harsh or extreme than a decision that consigns a child to lose a parent and extended family under the toxic influence of the other parent who failed to recognize and support the child’s need for two parents.” Warshak, “Ten Parental Alienation Fallacies” (2015), supra, at 244. A version of this article originally appeared in the February 2020 issue of the State Bar of Michigan’s Family Law Journal. is the owner and managing partner of Joshi: Attorneys + Counselors. He also serves as Publications and Content Officer for the ABA’s Section of Litigation and a senior editor of Litigation, the flagship journal of the Section. American Bar Association | /content/aba-cms-dotorg/en/groups/litigation/committees/family-law/articles/2020/spring2020-no-contact-orders-in-parental-alienationcases Ashish Joshi Copyright © 2020, American Bar Association. All rights reserved. This information or any portion thereof may not be copied or disseminated in any form or by any means or downloaded or stored in an electronic database or retrieval system without the express written consent of the American Bar Association. The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the positions or policies of the American Bar Association, the Section of Litigation, this committee, or the employer(s) of the author(s).

0 Comments

Traditional forms of therapy are not sufficient to address Parental Alienation. Disenfranchised Grief Within the Walls of Parental Alienation by Paul Michael Marinello | Jul 13, 2022 | 12 Step Programs, CPTSD, Gaslighting, Grief, Healing, Narcissistic Personality Disorder, Parental Alienation |

“I will admit, in my darkest moments my hope for others is much clearer than my hope for myself.” Anna-Maija Lee For the purposes of understanding this post, please review the following terms as it comes to parental alienation, alienating parent (a parent or loved one that uses forms of abusive behavior to assist in convincing a child the other parent is not worthy), and targeted parent which is a parent that has been partly or wholly eliminated from their child(ren)’s lives due to explicit targeting by the other parent. If you were asked a polling question where you swore to be truthful, take a moment to think of how you’d answer: What is grief, and how has it affected or influenced your life? Merriam-Websters definition seems a bit too lighthearted: deep and poignant distress caused by or as if by bereavement. National Cancer Institute states The normal response to a major loss, such as the death of a loved one. Grief may also be felt by a person with a serious, long-term illness or with a terminal illness. It may include feelings of great sadness, anger, guilt, and despair. Physical problems, such as not being able to sleep and changes in appetite, may also be part of grief. You can Google and receive many answers about the medical or socio-accepted belief on the definition of grief, however, for the purposes of this article, I am choosing to adopt Dictionary.com as defined: keen mental suffering or distress over affliction or loss; sharp sorrow; painful regret. (I also like the statement: a feeling of vacancy due to loss.) Grief is something normal that we all experience on a common basis. For many of us, we have been to funerals, wakes, and sit shiva, which served the purpose of allowing the families of those who have loved someone to honor someone’s light at the time of their passing. We understand this as grief and allow ourselves the moments we need in order to process a normal life cycle. For a parent that is alienated from their child(ren) grief is slightly skewed. The grief embodies not only a loss but the true disconnect of a normal and healthy relationship – one that all parents assume will last their lifetime. The grief also sticks to the heart in the way of guilt by association. What good parent would ever be alienated from their own child? The term disenfranchised is simple: to deprive (someone) of a right or privilege. As an alienated parent, disenfranchised grief plays a substantial part in everyday life. As parents, we grieve for the loss of our children, yet the unintended circumstances surrounding the reason for the vacancy are what lead to disenfranchisement. When we lose a loved one to a natural occurrence we qualify and quantify our feelings very succinctly. “I recently lost my mom, so I am going through a bit of an emotional time.” This seems like a common-sense answer you may have given or received a number of times throughout your lifetime. It’s topical in nature for a reason: even if the passing of an individual who you once loved was under normal circumstances, others still have issues deliberately seeking to penetrate another layer. Some might say, “I’ll be here if you need me,” or another supportive answer. Yet rarely do we or are we asked to go a bit further. “What was your mom like?” A simple question that could garner a set of tears or perhaps even a humorous story about mom. (There is nothing wrong with either or both.) Some tend to shy away from these follow-up questions simply as a defense mechanism. It is to protect both ourselves from getting emotional and showing weakness while we are trying to lift someone up from despair. We are also perceiving that if someone is emotional at the time, we are partly responsible for adding to their pain. I am not sure any of this is true. When an alienated parent is asked how their children are in blindsight (the person asking has no idea that you have been alienated) the answers can come off easily. During the beginning stages of complete alienation, I might have said that she was fine, studying and working while living with her mom. That usually keeps folks at bay and can often lead to some less traumatic discussion. Make no mistake, whether an alienated parent is asked by someone they love, a therapist, a friend – whether the person knows – we immediately go through a set of answers in our head to help them understand. Interestingly, most of these responses stay inside. I realize how ineffective this strategy is. However, a targeted parent must remain prepared for the inevitable; despite its prevalence for generations (and proven time and again with science, fact, and undeniable theory) few actually want to discuss something ugly like being abandoned by your child(ren). It’s quite similar to talking openly about drug abuse or mental illness and its effect on one’s family life. We don’t like to discuss it because it is sticky. Trauma sticks to the walls inside your skin. We can fight it, or we can succumb to it, but we are always living with it. These family traumas make our grief disenfranchised; difficult or almost wholly misunderstood, and are often lined with family secrets, and troubling pasts, and at the center of it all – unfortunately, is not our child(ren), but the alienator themselves. The ultimate puppet master. I asked Shirley Davis, Chief Staff Writer, and Trauma Expert with CPTSD Foundation, about this specific type of grief. She added, “Originating with a narcissistic or emotionally unstable parent, parental alienation has the power to overwhelm and injure children. The alienated parent (perhaps the father) is made into a pariah when the other parent (perhaps the mother) makes disparaging comments to their children. Parental alienation causes children to grow up to be adults feeling grief and loss because they love the alienated parent and cannot process what has happened.” With generational familial disease, like parental alienation, healing from the trauma of grief can be overwhelming. Unlike finding online support groups for alcohol or drug abuse, mental health resources, and trauma support groups like CPTSD Foundation, when a targeted parent wishes to share – few can understand or even care to grapple with the thoughts we need to process. There are often times – when we do share with those outside our trusted walls that we feel our grief is minimalized. That is not a result of our feelings or truths, but the result of wondering what another might think to hear you have been estranged from your own child(ren). It’s a tough starting place, so my only urging is that alienated parents continue to tell their stories, align, and educate health care professionals, the legal system, and educational systems. When someone tells you they have been a victim of alienation, process those thoughts with an open mind. There are resources available to help you better understand what we survive through. One draining aspect is a continued sense of hypervigilance within our communication. With this hypervigilance, a steady stream of tension surrounds targeted parents on how to and with whom to communicate these feelings forming a somewhat isolating tendency. And, in my opinion, this is a tough place to reside. Find the people in your life that are willing and able to do the research to correctly identify your feelings – even if they don’t quite understand them. Written for and Inspired by the members of Parental Alienation Anonymous, for without you, my personal journey to find peace within would not have been restored. Paul Michael MarinelloPaul Michael Marinello serves as a writer and blog editor for CPTSD Foundation. Previous to this role he managed North American Corporate Communications at MSL, a top ten public relations firm where he also served on the board for Diversity & Inclusion for a staff of 80,000. Paul Michael grew up in New York and attended SUNY Farmingdale before starting a ten-year career at Columbia University. He also served as Secretary and Records Management Officer for the Millwood Fire District, appointed annually by an elected board of fire commissioners from 2008 – 2017. The Truth About Parental Alienation

KEY POINTS

Source: Michał Parzuchowski/Unsplash The academic study and practical treatment of domestic abuse are evolving. Historically, researchers and support workers have tended to adopt the view that domestic abuse is inherently gendered, with primarily male perpetrators causing harm to primarily female victims. However, some recent research suggests that female-perpetrated domestic abuse may actually be as prevalent as male-perpetrated cases, leading this field to re-evaluate how it studies and addresses its core subject. This flipping of the perpetrator statistics comes in lockstep with an expanded view of domestic abuse, which is now an umbrella term that not only refers to physical violence, but also encompasses emotional abuse, blackmail, financial coercion, sexually-based manipulations, and coercive control of a partner's way of living. This broadened definition has been largely uncontroversial, as most people agree that these behaviors are abusive. However, one topic that has been increasingly discussed and disputed is that of parental alienation. What Is Parental Alienation? At its most basic level, parental alienation refers to the process by which a child unjustifiably aligns himself/herself with one parent, and expresses hatred or rejection of the other, during a separation or custody battle. This is typically driven by behaviors exhibited by the aligned-to parent that are designed to manipulate the child's beliefs and perceptions about the alienated parent, and the distortion or erasure of any positive memories that they might have about them. According to one representative survey published in 2019, more than one-third of parents feel somewhat alienated from their children in this way, with 22 million Americans (equating to around 7 percent of the population) reporting having a non-reciprocated alienated relationship with their offspring. Members of this latter group suggest that they are being alienated from their children without enacting any alienating behaviors. Around four million children are said to be alienated from one of their parents. Thus, parental alienation is viewed by many as an important social issue to explore and resolve. Dr. Jennifer Harman—an associate professor in psychology at Colorado State University, and world expert on parental alienation—recently published an overview of current research and theories underlying parental alienation in the journal Current Opinion in Psychology. When I asked Dr. Harman about the current science on this topic, she highlighted why it was important for her to conduct a review: article continues after advertisement. The goal of this review paper was to review all publications with empirical evidence on parental alienation to get a clear understanding of what we do know on the topic, and how people around the world have been studying the problem. This is important, because there are advocates around the world who are pushing legislation and policies claiming there is no scientific support for parental alienation. That is false information, and should not serve as a basis for laws that affect millions of children and families affected by this form of family violence. From recent work, it is unclear whether mothers or fathers are more likely to be the targets of parental alienation, though anecdotal evidence and some older research suggest that fathers are more likely to be alienated by mothers than vice versa in the course of a separation. However, the effects of alienation on targeted parents seem to be consistent irrespective of sex. Effects include the experience of grief over the loss of a relationship with the child(ren). Poor mental health outcomes are frequently reported, as are feelings of isolation and frustration. Alienation may also involve justice-related contexts, too, with those experiencing alienation often reporting dissatisfaction with how legal remedies to issues such as access and child custody are reached. Children at the center of parental alienation cases also experience a cascade of losses, according to Dr. Harman's research. This begins with a corruption of the child's reality and a disruption of their identity, through to the loss of extended family and community. The effects of such losses can be profound, with one paper led by Suzanne Verhaar (University of Tasmania, Australia) reporting how adults who experienced parental alienation as children often grow up to experience trauma responses, poor mental health outcomes, and a need to find coping strategies for emotional dysregulation. Why the Controversy? Given the evident effects of parental alienation on both targeted parents and their children, it is perhaps surprising to learn that there is a controversy over its existence. Dr. Harman said: "The take-home message [from her work] is that the research on this problem makes an important contribution to the existing research on child development and family conflict, and that it is no longer tenable to argue that there is no scientific support for the problem. "She did not wish to comment on the motives of those doubting the validity of parental alienation as a concept, but an online search suggests that some such doubts may come from some charities and activists who speak out about the domestic abuse of women. For example, Women's Aid UK has called parental alienation a "harmful and dangerous concept" that is used to counter accusations of domestic abuse being made by a parent who claims to be being alienated. It appears that the ideological battle over the notion of parental alienation is being fought, in part, between those studying the topic on the one hand and those with concerns about its weaponization on the other. This is not surprising, and is consistent across many areas of socially contested research. One might hope that future work looks to reconcile the science with such concerns, and look to eliminate the misuse of "parental alienation" as an accusation in arguments during separations while also supporting those who are legitimately experiencing these behaviors. Moving Forward Moving forward, Dr. Harman and her team are developing new ways of studying parental alienation. In response to critiques about the quality of research in this area, she said: We found similar proportions of studies that used different methods, sampling strategies, and measurement techniques, making claims by critics of parental alienation that the entire field is methodologically flawed wrong. We are now working on a follow-up review of more studies published since 2020 (when our literature search stopped), and are evaluating the quality of all of the studies using an appropriate evaluation approach used for fields where both qualitative and quantitative research is conducted. As the debate over the scientific and social status of parental alienation rumbles on, it is difficult to see a societal consensus emerging any time soon. A potential route out of this roadblock may be for competing teams to engage in adversarial collaborations, where both sides agree on a set protocol of study in advance, and a joint interpretation of the data. However, in the background are still those parents who, irrespective of the science, experience loss and separation from their children. The effects on them and their families will continue until services recognize the effects of alienation—real or perceived—and act to improve relationships within feuding families. References Harman, J. J., Leder-Elder, S., & Biringen, Z. (2019). Prevalence of adults who are the targets of parental alienating behaviors and their impact: Results from three national polls. Child & Youth Services Review, 106, 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2019.104471 Harman, J. J., Matthewson, M. L., & Baker, A. J. L. (2022). Losses experienced by children alienated from a parent. Current Opinion in Psychology, 43, 7-12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2021.05.002 Harman, J. J., Warshak, R. A., Lorandos, D., & Florian, M. J. (2022). Developmental psychology and the scientific status of parental alienation. Developmental Psychology. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0001404 Lee-maturana, S., Matthewson, M., Dwan, C., & Norris, K. (2019). Characteristics and experiences of targeted parents of parental alienation from their own perspective: A systematic literature review. Australian Journal of Psychology, 71, 83-91. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajpy.12226 Verhaar, S., Matthewson, M. L., & Bentley, C. (2022). The impact of parental alienating behaviours on the mental health of adults alienated in childhood. Children, 9, 475. Costa, D., Soares, J., Lindert, J., Hatzidimitriadou, E., Sundin, O., Toth, O., Ioannidi-Kapolo, E., & Barros, H. (2015). Intimate partner violence: a study in men and women from six European countries. International Journal of Public Health, 60, 467-478. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-015-0663-1 False Allegations of Abuse During Divorce: The Role of Alienating Beliefs

November 23, 2021 Alan D. Blotcky, PhD How can mental health experts help identify false allegations and alienation during divorce proceedings? couple_kieferpix/Adobe Stock FORENSIC PRACTICE As a clinical and forensic psychologist, I have been involved in hundreds of cases of divorce and child custody. The topic of false allegations of abuse is a complicated and thorny one that deserves much attention. In particular, there needs to be a focus on the alienating beliefs that often underly and compel false allegations. False allegations of abuse are an all-too-common phenomenon during divorce and child custody proceedings. One parent fabricates a false allegation against the other parent to gain leverage in court and to undermine the parent-child relationship going forward. The frequency of false allegations in custody cases is not fully understood, with estimates ranging from 2% to 35% of all cases involving children.1 Whatever the percentage, attorneys, judges, and mental health experts all know firsthand that it is a vexing problem in court cases. And nothing can disrupt, sidetrack, or impede a case more than an allegation of abuse that eventually proves to be false. Parents never admit to their conniving and harmful behavior during a legal action. As such, proving an allegation is false can be extremely challenging. Why? Because a false allegation is hatched in the mind of the offending parent, who then enlists the help of their child to unwittingly carry out the plot. The intent is to harm the other parent, but to do so as if the offending parent is the real victim. Parents know that an allegation of abuse has the potential to help them win their case, which is their ultimate goal. Unfortunately, being honest and fair is not always a virtue in a contentious child custody case. Detecting a false allegation is critical because judges can be swayed by the accusation, even if it is not substantiated by the evidence. More often than not, custody decisions go in favor of the accusing parent.2 So, uncovering and exposing a false allegation is vital in making sure the offending parent is not rewarded for his or her destructive behavior. Discovery of Alienating Beliefs The surest way to prove a false allegation of abuse is to uncover the alienating belief system of the offending parent. Alienating beliefs often underlie a parent’s decision to fabricate a false allegation against the other parent. With careful interviewing and psychological testing, these beliefs can be brought to the surface. A mental health professional is best suited to address this clinical problem. It takes patience and a probing attitude by the clinician to elicit alienating beliefs that are being hidden from view by the offending parent. Sentence Completion Series is one psychological instrument that will elicit thoughts, feelings, actions, intentions, and motivations. In interviewing, hypothetical questions, a focus on nonverbal cues, and exploration of apparent discrepancies can be productive. Here are 7 common alienating beliefs that occur in false allegations: 1. “I am afraid our child will love you more than me and will want to live with you.” 2. “I want my child all to myself.” 3. “If you don’t want me, you don’t get our child, either.” 4. “I want to exact revenge on you, and what better way than to deprive you of your child?” 5. “I don’t want my child to be anything like you.” 6. “I’ve been the real parent in this family, not you.” 7. “I don’t want my child to love their new stepparent because I might be pushed out.” The Many Implications There are important implications to consider in cases of false allegations of abuse. First, the desire to alienate the child from the other parent is at the core of most false allegations of abuse. And, when a parent makes multiple false allegations during a legal proceeding, you can bet that alienating beliefs are in play. Yet, it is important to note that not all false allegations are due to alienating motives. Sometimes, for example, a parent may over-interpret a comment or report from a child, thereby jumping to an erroneous conclusion. Rather than clarifying the benign situation, the parent makes what proves to be a false allegation. Other examples exist where alienation is not a major component in a false allegation.3 Second, a child needs to love both parents without impediment or interruption. Being caught in a loyalty fight is damaging, as a child’s long-term adjustment is dependent upon having a close relationship with both parents. Anything short of that is unacceptable. A false allegation of abuse can go a long way to disrupt a child’s relationship with the accused parent. Loving that parent may become strained or even impossible going forward. Thus, a false allegation against a parent can have a tragically negative impact on the child.4 Third, offending parents tend to view their children as possessions to be controlled and manipulated. They see them as extensions of themselves. That is not parental love, but rather, narcissistic self-absorption. It is the offending parent’s hostile needs and motivations that are the real problem in these cases, not the rejected, victimized parent. Offending parents lodge false allegations against the other parent to meet their own needs, not their child’s. Teaching a child to be a victim under false pretenses can set the stage for a lifetime of victimhood for the child. Fourth, vindictiveness is a malignant emotion that causes great pain, sorrow, and unhappiness in any relationship. Being consumed with vindictiveness is profoundly unhealthy. It has nothing to do with love and care for the child. Vindictiveness is common in false allegations of abuse. What is portrayed as protectiveness of the child is actually hostility and destructiveness toward the other parent, with little genuine concern for the child’s best interest. Fifth, false allegations of abuse must be stopped as soon as possible for the child’s wellbeing. If they are not stopped, the offending parent’s pernicious behavior will gain steam and impact over time. False allegations cannot be condoned in any way. Several courses of action are reasonable: limited parenting time, supervised visits, change of custody, court-ordered therapy, and others. Turning a blind eye to a false allegation of abuse is not an option. Finally, judges and attorneys need to be educated about the seriousness and deleterious consequences of false allegations of abuse. Mental health experts can help inform, explain, and guide during the legal proceeding or at trial. False allegations and alienation are highly disruptive to the wellbeing and mental health of the child. Concluding Remarks It should be reassuring to know that alienating beliefs can be uncovered and exposed. That is the key to unlocking the “proof” of a false allegation. Without exposure, a child custody case can be hijacked by a false allegation, and the child’s wellbeing may be lost in the confusion. After all, a child’s future can be at stake. This is the first installment in Dr Blotcky’s new column, “Forensic Practice.” Feedback and suggestions for future articles can be sent to [email protected]. Dr Blotcky is a clinical and forensic psychologist in private practice in Birmingham, Alabama. His specialty is false allegations of abuse and parental alienation. He can be reached at [email protected]. References 1. King DN, Drost M. Recantation and false allegations of child abuse. The National Children’s Advocacy Center. 2005;1-45. 2. Meier JS, Dickson S, O’Sullivan C, et al. Child custody outcomes in cases involving parental alienation and abuse allegations. GW Law Scholarly Commons. 2019;1-30. 3. Bernet W. False statements and the differential diagnosis of abuse allegations. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1993;32(5):903-910. 4. Brooks SK, Greenberg N. Psychological impact of being wrongfully accused of criminal offences: a systematic literature review. Med Sci Law. 2021;61(1):44-54. |

Archives

February 2024

Categories

All

|

||||||

RSS Feed

RSS Feed